There were seven buckets of different size and color on the tile floor - one for each roof leak and true musical note, A B C D E F G. When raindrops landed in the buckets, it sounded like an orchestra of analog Four Tet backed with an endless loop of Lo Fi precipitation.

When you live in a UNESCO World Heritage Site, odds are your roof is going to leak.

Welcome to the Ensōnomics rain drop edition. Cue the noise machine.

Rain has been sharing stories for a while - roughly four billion years.

In 2024, scientists published a study in Nature Geoscience that analyzed zircon crytals from the Jack Hills formation in Western Australia. The zircon crystals showed unusually light oxygen isotopes, high ratio of ^16O relative to ^18O, a hallmark of fresh water interaction rather than seawater. This also indicates rain fell on exposed land surfaces, meaning continental crust existed around 4 billion years ago. The findings challenge the earlier view that Earth was entirely covered by ocean during the Hadean eon and open the possibility that the presence of fresh water and land could have provided a setting conducive to the emergence of life within 600 million years after Earth's formation.

75% of the earth is covered with water, and this same water has been recirculating through the planet for billions of years via the water cycle.

You might think about it this way - an ensō of nature, that began in the sky, crossed paths with you - and just for a moment, as that one rain drop lands on your skin, you're connected to the ancient and all that comes with it.

I like to walk in the rain. And it’s still rainy season here. The sidewalks are slippery so it pays to be mindful. If you’re crossing a street on an east west axis, your shoes are gonna get wet. As in soaking.

Here’s what it can look like in El Jardin. The Mariachi’s? Porfa - can’t stop, won’t stop. The music continues rain or shine.

Not all rain makes it to the ground. Sometimes it evaporates midair. This phenomenon is called virga. You can see it stretching like tendrils beneath the clouds.

Sometimes it’s a light rain. Sometimes the rain falls heavy. Raindrops fall at varying speeds depending on their size, with larger drops falling faster. In still air, typical raindrops fall at speeds between 7 and 20 miles per hour, while very small raindrops may fall at only 1 mile per hour.

Terminal velocity is the maximum speed an object reaches when falling through a fluid - when the force of gravity is balanced by the drag force and buoyancy. .

The terminal velocity of a typical raindrop can be estimated using a formula from fluid dynamics:

v = √(2mg / ρACd)

Where:

v is the terminal velocity,

m is the mass of the drop,

g is acceleration due to gravity,

ρ is air density,

A is the cross-sectional area of the drop,

Cd is the drag coefficient.

For a standard 2 mm raindrop, the terminal velocity is around 6.5 meters per second. That’s about 14.5 miles per hour.

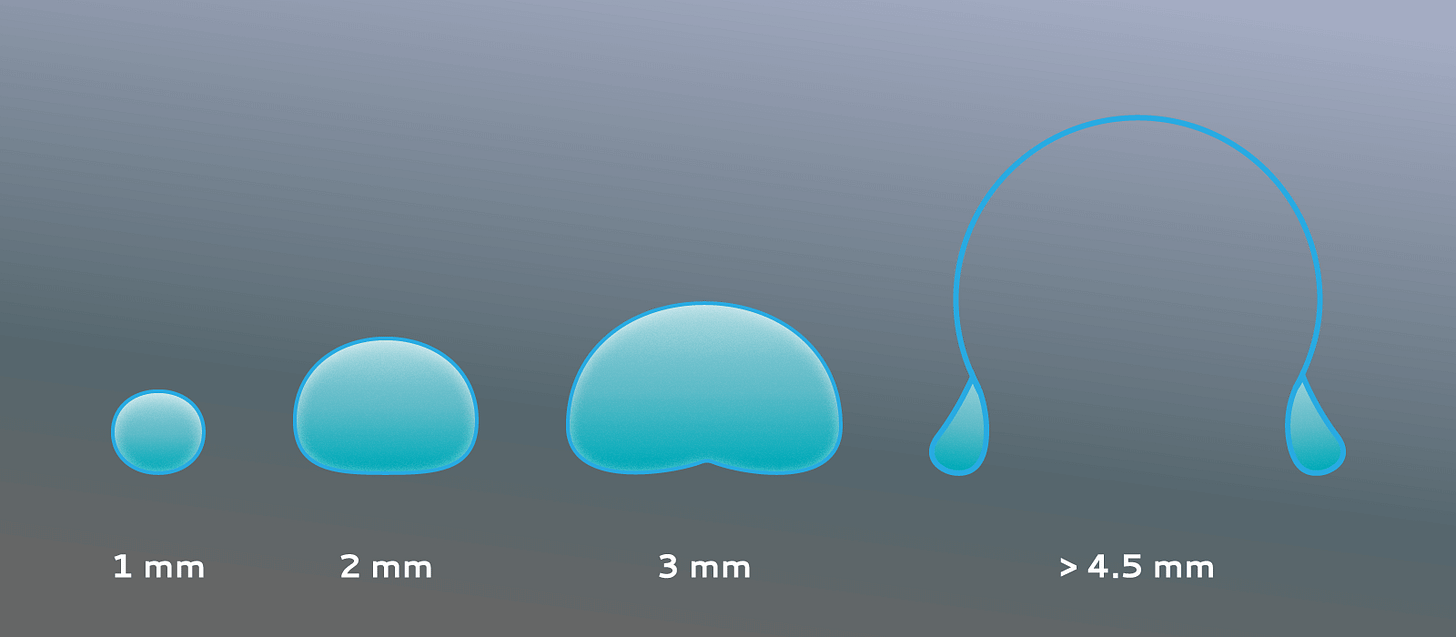

Raindrops aren’t teardrop shaped.

Most people imagine raindrops as teardrop shaped, but in reality, falling raindrops resemble puffy hamburger buns - the result of fluid dynamics, surface tension, air resistance, and gravity interacting in motion. When a drop first detaches from a cloud, it is nearly spherical due to surface tension, which pulls water molecules into the most compact, stable form. However, as the droplet falls, air pressure pushes up against its bottom, flattening it into a shape that’s more dome like than round.

According to NASA, droplets smaller than 1 mm remain spherical, but as size increases, the shape distorts. By around 4.5 mm, the droplet flattens significantly and may even split into smaller drops due to instability from drag forces. This is known as the breakup limit. The U.S. Geological Survey confirms that larger drops, about the size of a pencil eraser, rarely fall intact for long.

Temperature, humidity, and altitude also affect a droplet’s behavior. Warmer air can hold more moisture, allowing for larger drops to form. Wind turbulence can shear droplets apart mid-fall, while dust particles or pollution can serve as condensation nuclei, shaping how the drop initially forms.

The precise shape of a raindrop in motion is a fleeting compromise between cohesion and collapse. It is not only a product of water, but of the sky’s invisible architecture, air currents, gravity, and pressure, painting a cooperative ensō on its way to earth.

When the rain finally hits the ground, there’s a bonus experience. The earthy scent that often follows rainfall, petrichor, comes largely from a compound called geosmin. This molecule is what gives soil its familiar, fresh aroma. It’s not rain that carries the scent, but rather how rain interacts with the earth below. Geosmin is produced by a type of soil dwelling bacteria known as actinomycetes, especially those in the Streptomyces genus. These microorganisms release geosmin into the soil, where it quietly accumulates during dry spells.

When rain finally arrives, its droplets strike the dry ground with enough force to create tiny air pockets on the soil’s surface. Trapped inside these bubbles are geosmin molecules, along with plant oils and other volatile compounds. As the raindrops hit, the bubbles burst, and a fine aerosol mist carries these aromatic compounds upward. This release mechanism is so effective that people can often smell rain before it arrives, especially if the wind is moving in the right direction.

Petrichor is more than just geosmin, though. Plant oils that have collected in dry soil add their own subtle notes to the blend. And when lightning splits the sky during a thunderstorm, it creates ozone - a sharp, metallic scent that can mix with petrichor to produce that unmistakable storm scent.

Humans are incredibly attuned to geosmin. We can detect it at levels as low as 0.004 parts per billion. That means a single drop of geosmin diluted in an Olympic-sized swimming pool would still be noticeable to the human nose - perhaps a sensory relic from our ancestors whose survival might have once depended on sensing the rain.

And that physical charge you feel sometimes? You’re not imagining it. Rain is electric.

In 2023, a study published in Nature showed how raindrops on leaves generate electricity through contact electrification and the triboelectric effect. These two phenomena describe how electrons move when water touches organic surfaces, transferring charge between the liquid and the leaf. The initial moment of contact creates an electric imbalance, and as the droplet spreads and separates, that charge is left behind. The process is small in scale but measurable. On artificial leaves designed to mimic natural ones, scientists have recorded voltages up to 47 volts and currents as high as 17 micro amperes, enough to light a small LED with a single raindrop. The waxy cuticles and microscopic textures found on real leaves enhance this effect, creating more surface area for interaction. Living plants also produce detectable electrical signals when it rains. These signals are tiny but reliable, hinting at future applications for self powered environmental sensors. Such sensors could monitor rainfall, humidity, and pollution without needing batteries. The combined mechanical energy of raindrops and wind could even fuel micro generators in remote areas. As climate events grow more erratic, the discovery that leaves can act as miniature hydrovoltaic panels suggests that nature might help power its own observation. With every drop, the environment becomes both subject and sensor, an elegant ensō of motion, matter, and charge.

So the next time it rains, maybe don’t be in such a rush to avoid it. In the words of Langston Hughes, “Let the rain kiss you. Let the rain beat upon your head with silver liquid drops. Let the rain sing you a lullaby.”

The rainy season will be over soon.

I hope it rains today.

Japan’s Ensō of Rainy Day Transparency

When it rains in Tokyo, people often use clear umbrellas, especially the cheap plastic kind, for a mix of practical, cultural, and aesthetic reasons.

Tokyo is dense. On crowded sidewalks or train platforms, clear umbrellas let people see where they’re going. On rainy days, a clear umbrella lets you see the city, the sky, and the trees. You remain visually connected to the world around you. There's poetry in watching rain fall through a transparent dome.

You don’t block your own view or others. This cuts down on impromptu umbrella fencing matches and provides a sense of shared spatial awareness. Convenience stores like 7 Eleven sell clear umbrellas for around 500 yen (about $3–$4 USD). They're cheap, available everywhere, and bought impulsively when it starts raining. Because they’re everywhere, they’ve become the default.

Japanese aesthetics often favor minimalism and non intrusion. Clear umbrellas don’t clash with clothing or surroundings. They’re neutral, calm, and fade into the background. That fits the cultural emphasis on subtlety.

In many places, people leave their umbrellas in racks. Since clear umbrellas all look the same, it’s easy to take the wrong one by accident. Some people mark theirs with stickers or labels, but the clear style is so common it reinforces norms of trust and mutual respect. They may seem disposable, but in Tokyo, the clear umbrella is a soft solution to an urban challenge - functional, polite, and invisible by design.

A First Ballot Rain Song Hall of Fame

There is no shortage of songs about rain - and then there is Jimmy Page & Robert Plant with the London Metropolitan Orchestra.

To view, click on Watch on YouTube Icon located lower left

On Reflection

A puddle repeats infinity, and is full of light; nevertheless, if analyzed objectively, a puddle is a piece of dirty water spread very thin on mud.

The Endsō

it really is - and the smile on Page's face at the end...Madison Square Garden '73 was a close second.

Beautiful rendition of the Rain Song