Stuck.

Going nowhere fast.

Completely Frozen.

Cue Ernest Shackleton.

In 1914, a century before Wintergreen Parkas and Red Bull sponsorships, Ernest Shackleton set out to make the first land crossing of Antarctica, a journey across 1,800 miles of frozen desert, from sea to sea via the South Pole - and failed.

Instead, his ship, Endurance, was trapped and crushed by ice. He never crossed the continent. While history is full of explorers who achieved glory by conquering summits or reaching new worlds, Shackleton did neither.

And yet, more than a century later, Shackleton is viewed as one of today’s most revered case study icons. The reasoning lies not in what he accomplished, but in what he preserved. Every one of the 27 men under his care survived the expedition, despite being marooned in the most hostile environment on Earth for nearly two years.

Let’s be honest. The Antarctic is a place where human beings are not meant to live. Temperatures often drop below 34.4°C (-30°F) and winds are next level. During the dark winter months, the sun disappears entirely, plunging the landscape into a kind of lunar stillness. It was into this world that Shackleton and his crew of the Endurance sailed, only to become immobilized in the dense pack ice of the Weddell Sea by January 1915.

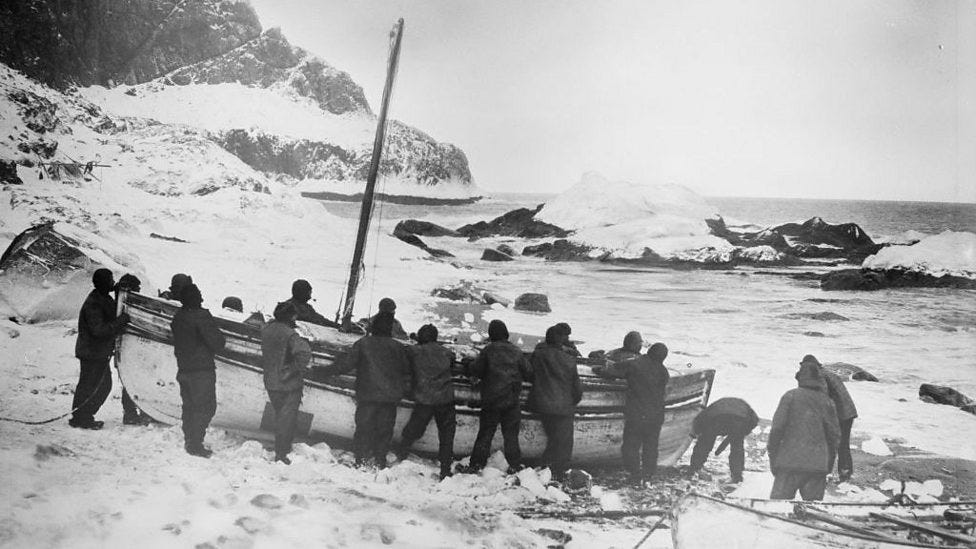

For 10 months they drifted, waiting for the spring thaw. But the ice intended otherwise. By October, pressure crushed the Endurance, splintering the hull like matchsticks. Shackleton watched his ship, and his expedition, disappear.

But this was where Shackleton’s leadership emerged, not in pursuit of glory, but in radical responsibility.

He pivoted. The mission was no longer exploration. It became about survive and advance. Just stay alive.

Shackleton understood morale was as essential as food and shelter. According to historian Alfred Lansing in Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage (1959), he monitored the emotional weather of the group with precision. He reassigned tent groups to prevent factions. He held a strict schedule - morning tea, communal meals, songs after dinner. When the group finally abandoned the ice and camped on Elephant Island, he chose to take the most difficult personalities with him on the next leg, a harrowing 800 mile open boat journey across the Drake Passage, so the remaining men could live in peace.

The voyage of the James Caird, a 22-foot lifeboat loaded with minimal rations, is one of the greatest feats of small boat navigation in recorded history. For 16 days Shackleton and five men endured the most difficult of conditions. The temperature hovered near freezing. Their clothes were soaked. Their beards froze to their faces at night. Yet somehow, they reached South Georgia Island. Shackleton and two others then climbed over its unmapped mountains and glaciers for 36 hours straight, finally reaching a whaling station where he could begin to launch rescue missions back for the others.

It took four attempts to reach Elephant Island again. Ice blocked the route each time. But finally, on August 30, 1916, Shackleton returned and brought every man home. Not one life lost.

That success, the survival of all parties, reframed the entire mission. What at first glance hovered on the edge of tragic became an epic human triumph. In 1921, Shackleton gave a brief, understated reflection on the ordeal, “Difficulties are just things to overcome, after all.” He died the following year, his body now buried in South Georgia at the abandoned whaling station of Grytviken where a toast of whisky at his grave is a tradition among travelers there.

Shackleton’s expedition, stripped of its original purpose, took on a deeper meaning when you looked past the surface metrics. Leadership theorists and thought leaders now study Shackleton not for his expedition strategy, but for his emotional intelligence. Harvard Business School teaches a case study on his methods. What they admire isn’t ambition - it’s attunement, the state of being aware of and responsive to something, particularly in the context of relationships and emotions. Shackleton didn’t rigidly cling to the goal. He responded to conditions in real time. He made decisions not from the top down, but from the inside out - and his leadership wasn’t drawn in a straight line - it was circular and centered - an ensō of ambition, wreckage and return, also a masterwork of imperfection and the beauty of incompleteness.

Modern life doesn't place most of us in crushing ice floes or storm tossed lifeboats. But it does deliver its own versions of challenges - projects and careers that stall, relationships that don't go as planned…life in all its glory and all part of the modern human experience. Shackleton's story reminds us that even in those moments, the real measure is not whether we reach the intended destination, but how we show up along the way. It can be the underlying theologies and values that move up the org chart.

Here’s five of many takeaways.

1. Optimism – Shackleton preached pragmatic optimism and liked to surround himself with cheerful, optimistic people

2. Keep the naysayers close – when deciding who would live with him in his tent on the ice he went against every human instinct and paired himself with those who challenged his authority

3. Everyone should feel part of the solution – Shackleton made sure everyone was doing something worthwhile to get out of the situation

4. Be self-sacrificing – Shackleton never let his men go without a comfort it was in his power to give

5. Remember the Mental Medicine – Shackleton made sure the crew retained their sense of humor and went to great lengths to hold small celebrations

To walk in Shackleton’s footsteps is not to brave ice or hunger. It is to commit to care when it’s hardest - to adapt with grace and find completeness in incompleteness. We may never lead 27 souls out of a polar prison. But each of us, in our moments of failure, can learn to endure. And not just to survive, but to return from the expedition intact and whole.

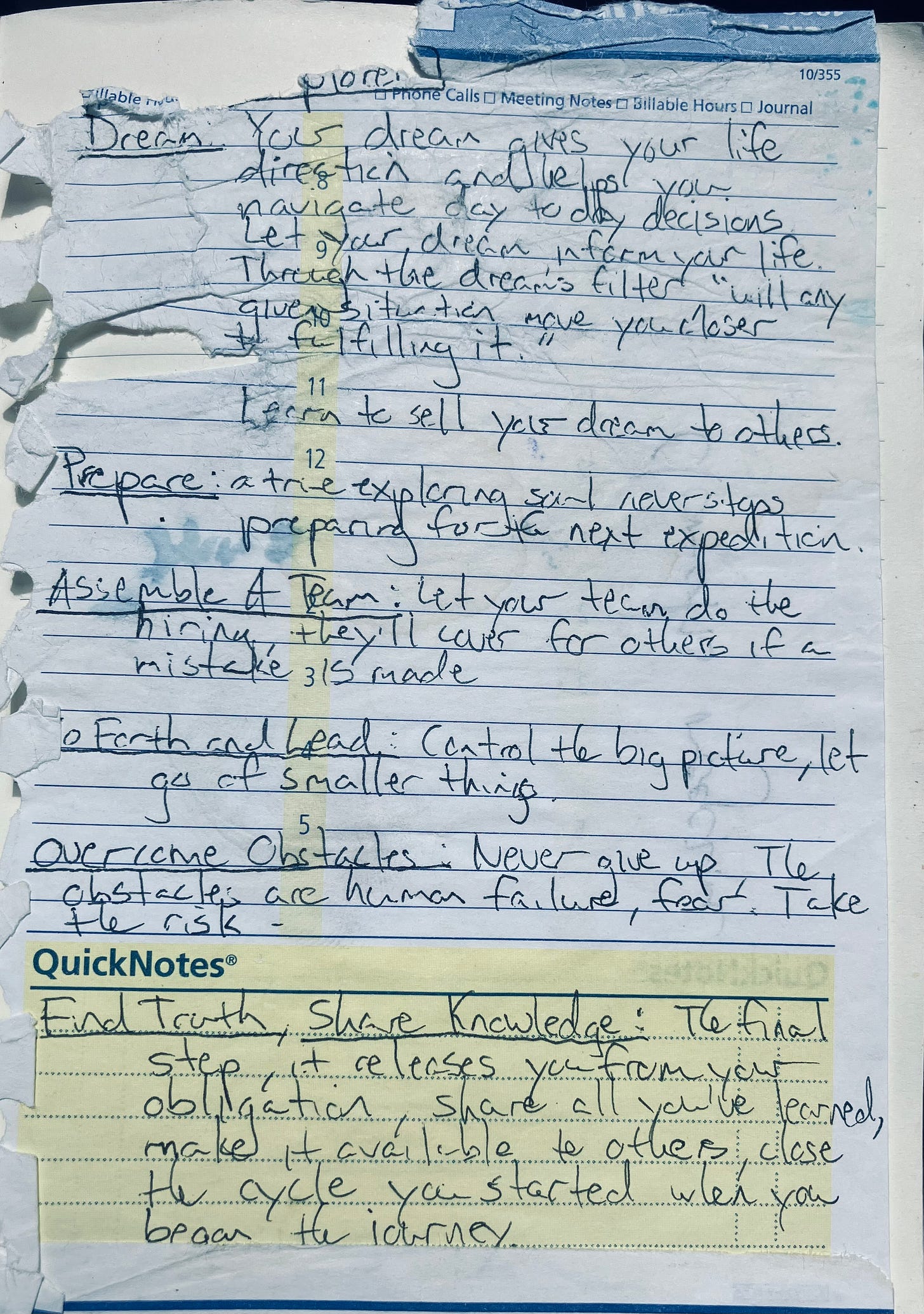

Your Dream Gives Your Life Direction

Robert Ballard is an explorer. He discovered the Titanic - while trying to locate two lost nuclear submarines. Here is a much handled page of notes assembled from a lecture some two decades ago. It pretty much speaks for itself.

Keep Looking

“I think you grow up twice, The first time happens automatically. Everyone passes from childhood to adulthood, and this transition is marked as much by the moment when the weight of the world overshadows the wonder of the world as it is by the passage of years. Usually you don't get to choose when it happens. But if the triumph of this weight over wonder makes the first passage into adulthood, the second is the rediscovery of that wonder despite sickness, evil, fear, sadness, suffering - despite everything. And this second passage doesn't happen on its own. It's a choice, not an inevitability. It is something you have to deliberately find, and value, and protect. And you can't just do it once and keep it forever. You have to keep looking.”

- Nate Staniforth

From Here Is Real Magic: A Magician's Search for Wonder in the Modern World

The Endsō